Commune loves Japan: Ikebana

We’ve been spending a great deal of time in Japan and we’d like to highlight a few things we love. This is a focus on one of the most fascinating traditions, hailing from the city that’s consumed us: Kyoto.

02.14.2020

We’ve been spending a great deal of time in Japan over the past five years and as our projects there culminate we’d like to highlight a few things we love.

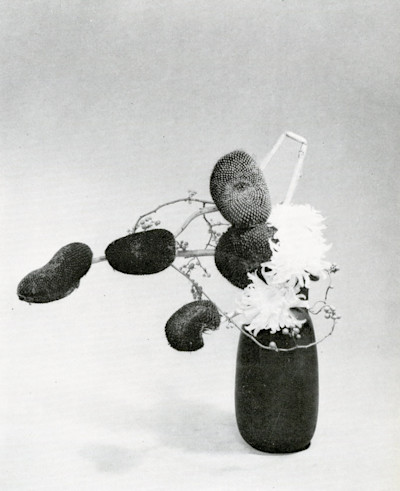

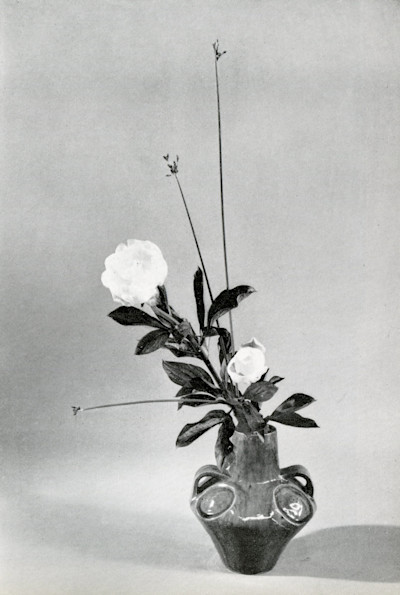

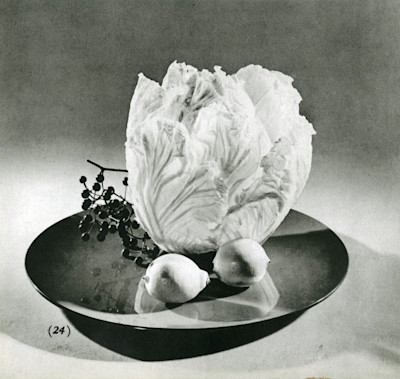

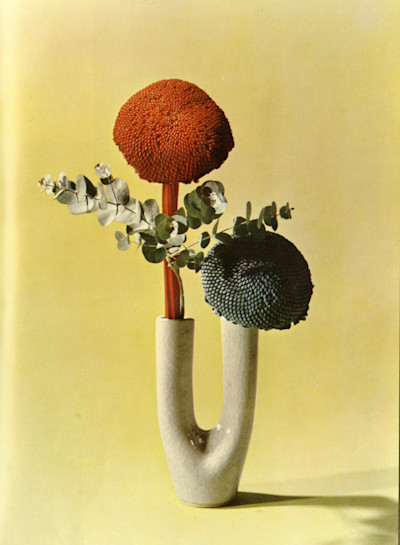

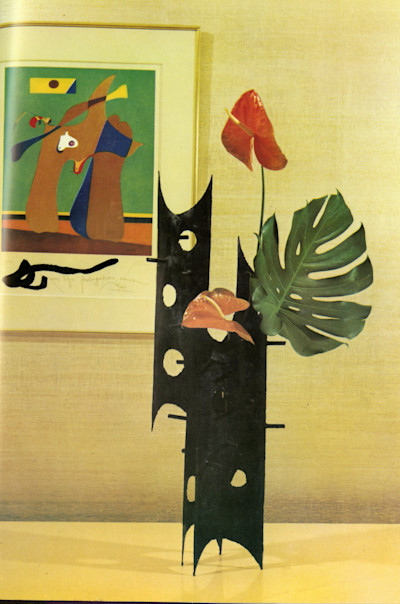

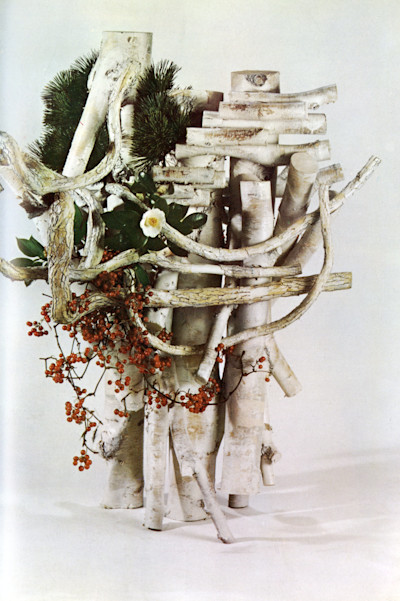

This week we’re focusing on something born right out of the city that’s consumed us: Kyoto. It’s a practice called ikebana, or “making flowers alive”. We find ourselves completely and utterly obsessed with its core principle that one small object (in this case a plant or a flower) can show us the depths of the beauty in our universe. Nothing superfluous need be present, a stem or leaf itself is enough to understand the beauty. This restraint and respect for a humble material is something we so admire about Japanese design, and ikebana embodies it fully.

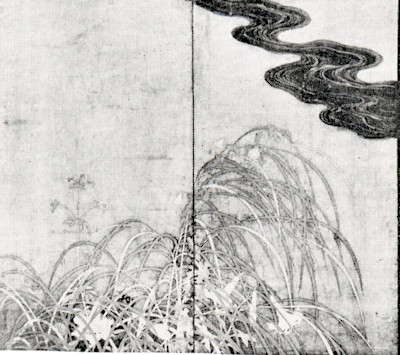

The trajectory of ikebana as practiced in Japan follows the growth of Buddhism from the sixth century onwards. Once Buddhism arrived by way of China, many people converted, temples were built, and the ritual of leaving offerings for Buddha quickly took hold. These offerings often arrived in the form of flowers, and naturally, the flowers began to be arranged and sculpted in specifically meaningful ways. This history is rooted in the Rokkaku-do temple in Kyoto, where the earliest school for ikebana was formed: Ikenobo. It was there where the principles of ikebana were established, which now act as a set of guidelines by which to practice ikebana everywhere. These rules dictate shape, line and form and demand that the arrangement is naturally graceful in its simplicity, but always reflective of the maker’s emotions. This relationship of the maker to the arrangement is critical, as the makers are asked to arrange the ikebana in quiet solitude in order to emphasize clarity of emotion. In terms of color, each stem is evaluated for its respective physiological effects (the messages the color gives to us from nature itself), and is left as minimally altered as possible. In short, the arrangement should feel ‘found’ instead of ‘forced’.

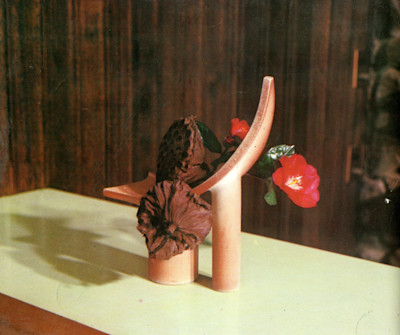

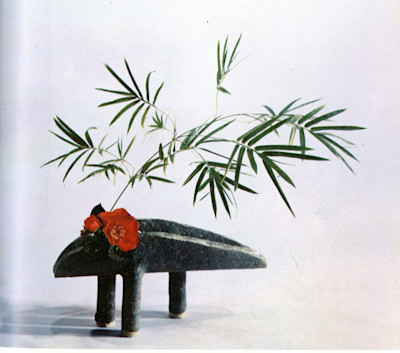

There are thousands of schools of ikebana at this point, but they all harken back to a few key principles: simplicity, balance, and manifesting an aesthetically pleasing prepresentation of heaven/earth/humanity (each aspect of the arrangement represents one part). Since the point of ikebana is for the maker to connect to nature, the latter three symbols are critical in understanding why it’s such a simple arrangement and why it’s so minimal. For example, in the Moribana style, the tallest branch represents heaven, the medium height flower or branch represents the human, and the lowest height branch represents the earth. They exist in beautiful harmony. The shallow bowl they sit in exists to remind the maker and the viewer that this is a serving (offering) and not just a pretty arrangement.

The images here are from three books we have from the 1960s. Beyond the fact that they show textbook examples of ikebana, we think the colors and proportions are out of this world.