From the Studio: Mick Haggerty

Turning Failure Into Success

11.15.2025

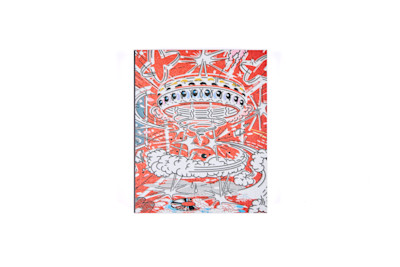

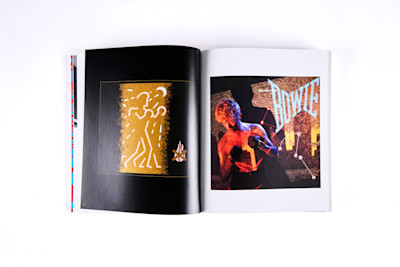

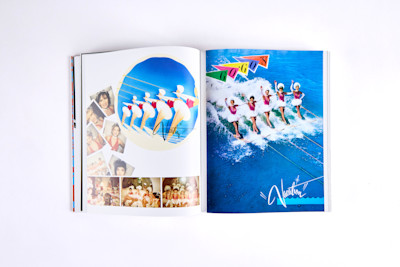

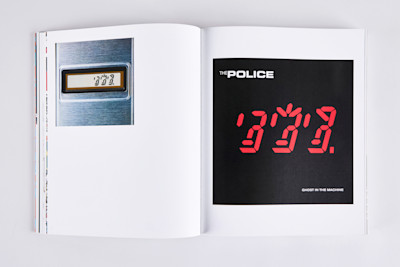

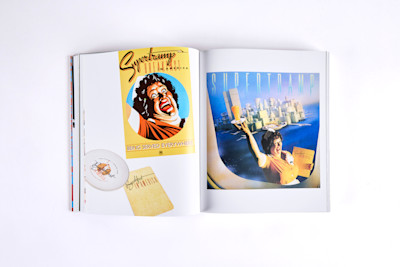

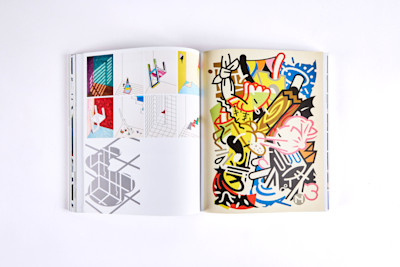

Mick Haggerty is a visionary British graphic designer known for his inventive, witty approach to visual communication. Blurring the boundaries between art, design, and pop culture, he crafted iconic album covers for artists like David Bowie and The Police, as well as bold work in film and advertising. Haggerty’s style combined sharp conceptual thinking with playful, unconventional execution, leaving a lasting mark on 20th-century visual culture and inspiring generations of designers to think beyond the expected.

You trained at the Central School and the Royal College of Art in London before moving to Los Angeles in the early 1970s. What drew you to design in the first place, and what was happening in Britain at the time that shaped your early visual sensibility?

Nothing like surviving near annihilation in a World War to make a fossilized little island like Britain wake up and try things differently, and I was lucky to be one of the children of that joyous recoil. A cultural revolution and social experiment promoted in large part by great artists and designers of all kinds teaching in schools and universities that the government paid students to attend. Just add the discovery of Black American music, and you had kids like me that thought art and music could change the world.

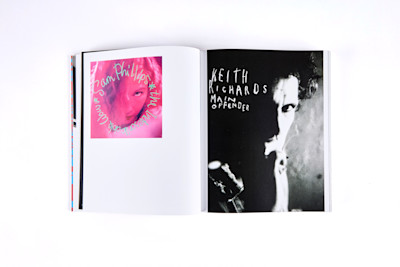

You’ve worked with artists ranging from David Bowie and The Police to Supertramp and the B-52s. What was your process for translating a musician’s sound or persona into a visual image? Can you describe a collaboration that particularly challenged or surprised you?

I earned a reputation for not necessarily reinforcing a performers persona but changing it up a bit. The “translation" was usually just the challenge of steering everyone to what I thought was the best concept, but in the best cases an offhand remark added a missing magic element. Almost everyone I’ve worked with has left their mark on the process. Bowie was fearless and joyful. He taught me that if it's not fun, don’t bother. John Lydon was a gentleman and a delight. Richard Thompson too. I really enjoyed Robert Fripp and Adrian Belew. I give thanks to everyone who allowed me to work with them, for the opportunity and taking the risk.

Over the years, you’ve moved fluidly between roles — art director, designer, illustrator, and educator, and artist. Do you see any delineation between these roles or do they all inform each other?

They are all a chance to say “what if - ?…”

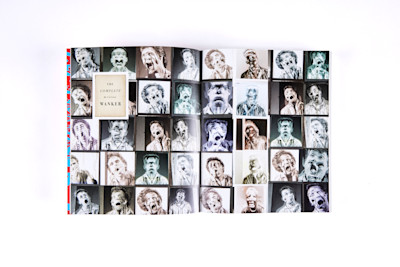

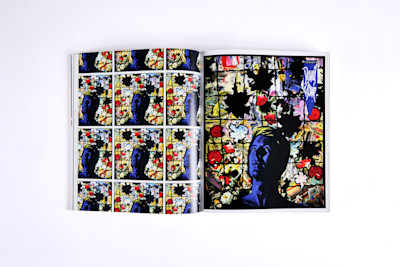

In recent years, you’ve devoted more time to your own visual experiments and publications like MXWX. How different is your mindset when you’re creating work for yourself rather than for a client or musician?

I’ve always really been making work for myself, except back then someone else printed, published and distributed it. They even put music inside and gave me money. I miss those parts for sure.

Can you tell us how you came to know Roman and Commune?

Who?

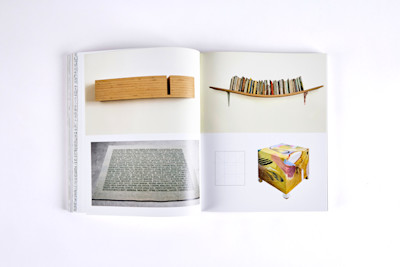

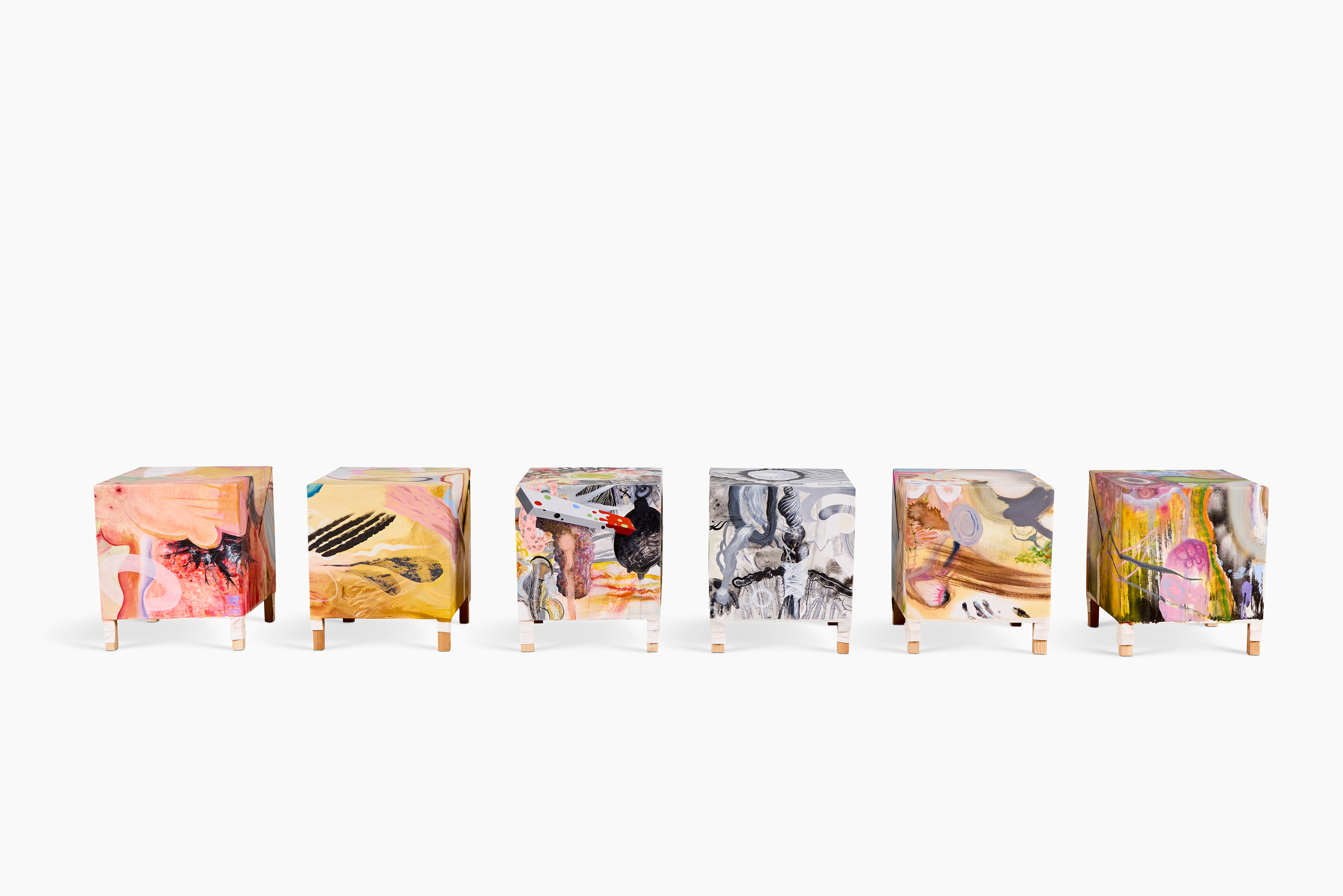

We are really excited about your tables! How did the idea to make furniture from paintings come about?

I’m excited about them too. Painting is so damn hard and there are many casualties along the way. The studio looks like a graveyard of good intentions and wasted time. Failures. What to do with them? I realized that a painting contains all the parts necessary to be repurposed as something useful. A handsome side table for example. The stretcher bars become its frame, the canvas its cover, and with few staples - a failure no more! After all the creativity I expended to no avail trying to make a painting, it’s a treat that without any “creativity" at all, watching it take its new shape as furniture. So many accidental alignments and unintended framings. I also realized that it has been transformed from perhaps being a painting of a table, to a table of a painting.

You’ve often spoken about reinvention and avoiding repetition. What continues to keep you curious about making images today?

Working commercially, I’ve was always interested in making images that said something, whether profound or stupid and then just searching out the technique and material most effective to communicate that message as loudly as I could. Hence the necessity of constant change. Working now, I find that’s not so interesting. I try to work in a much less premeditated way, trying instead to listen and perhaps hear what those materials and techniques might have to say to me.

How do you see the role of design evolving for future generations?

I'm not clear what design is now, let alone in the future, but I’ll bet humankind will always feel compelled to make visual images by some method for some reason and to give that a name. Might not be design.

What inspires you these days?

I’m going to stay with turning failure into success.